American Pipit

General Description

American Pipits are small, brownish, streaked birds that are sparrow-like in appearance, but with much thinner bills. Males and females look alike. They are slender, with gray-brown backs and buff-colored breasts. During the breeding season, their breasts may be streaked or unstreaked, but outside the breeding season, they are typically more heavily streaked.

Habitat

American Pipits are open-country birds in all seasons. They breed in alpine areas, near seeps, streams, lakes, or wet meadows. During migration and winter, they come down into the lowlands and can be found on beaches, marshes, agricultural fields, short-grass prairies, and mudflats.

Behavior

American Pipits walk or run along the ground and forage in flocks outside the breeding season. They wag their tails up and down and are easily identified by the double call-note given in flight. When flushed, they fly up, circle around, and come back down to the ground, descending in a stair-step pattern.

Diet

During summer, American Pipits eat mostly invertebrates. During fall and winter, American Pipits complement their diet with grass and weed seeds, which can make up half their diet during these seasons.

Nesting

American Pipits are monogamous, and pairs may form during migration or on the wintering grounds. They nest on the ground, usually in a sheltered spot, tucked under overhanging grass, a rock ledge, or other object. The female builds a cup-nest out of grass, sedge, and weeds, and lines it with finer grass, feathers, or hair. She incubates 3-7 eggs for about 14 days while the male brings her food. The female broods the young for the first 4-5 days, and the male continues to bring food for the female and the chicks. After brooding, the female joins in feeding the chicks. The young leave the nest after about two weeks, but stay close and are fed by both adults for another two weeks, after which they join loose flocks of other immature birds.

Migration Status

American Pipits are highly migratory and travel during the day in loose, straggling flocks. Fall migration begins in mid-September through October, when weather begins to deteriorate on the Arctic breeding grounds. American Pipits winter throughout the southern United States south to the tip of Central America. Birds return to the Arctic in the spring, with the peak migration occurring from late March through early May.

Conservation Status

While there is some suggestion of declining numbers, American Pipits are currently widespread and common. Global warming may allow these birds to winter farther north than previously, but it also may reduce and fragment existing breeding areas. Forest clearing has probably increased American Pipit migration and wintering habitat, but the draining and destruction of wetlands and livestock grazing have had negative impacts on these habitats.

When and Where to Find in Washington

American Pipits are present in Washington as breeders, migrants, and wintering birds. They are common breeders at high elevations in the Olympics and North Cascades, and at major volcanic mountains in the southern Cascades. In the Olympics, they are most common in the wetter, western alpine areas. They are common from Mount Baker to Harts Pass (Whatcom County), and on Mount Adams, Mount Rainier, and Mount St. Helens. They are common migrants in open habitats throughout the state from mid-April to early May, and then again from early September to mid-November. Small numbers winter in western Washington, and can be found in fallow fields or open, disturbed areas, and on beaches. A few wintering birds can rarely be found in the river valleys and lake basins of eastern Washington.

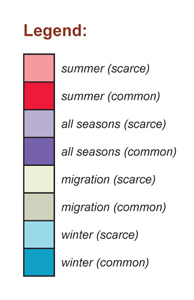

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | C | C | F | F | F | C | F | U | R |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | F | U | U | C | F | U | U | ||

| North Cascades | R | R | R | C | F | F | F | F | C | F | R | R |

| West Cascades | U | U | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | U | ||

| East Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | R | ||||

| Okanogan | C | C | F | F | C | C | C | U | ||||

| Canadian Rockies | F | U | F | C | C | U | ||||||

| Blue Mountains | U | U | R | |||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | F | U | F | F | U | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map